The COVID-19 pandemic, its recession and increased food costs have created a second, quieter epidemic: hunger. This hunger epidemic has hit schoolchildren the hardest as school closures cost them not only classroom time, but also the school breakfasts and lunches upon which they relied. During the pandemic’s early stage, 13% of Alabama families with children told the Census Bureau that they either sometimes or often didn’t have enough food to eat. Hunger rates were more than two times higher for Black and Hispanic families in our state.

Alabama schools and communities responded heroically to this crisis, preparing and distributing “grab-and-go” school meals across the state. The state and federal governments also did their part by creating a new food assistance program called Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer (P-EBT). Thanks to P-EBT and other federal programs like the expanded Child Tax Credit, the share of Alabama families with children who sometimes or often didn’t have enough to eat declined to 9% by the end of July 2021.

What is P-EBT?

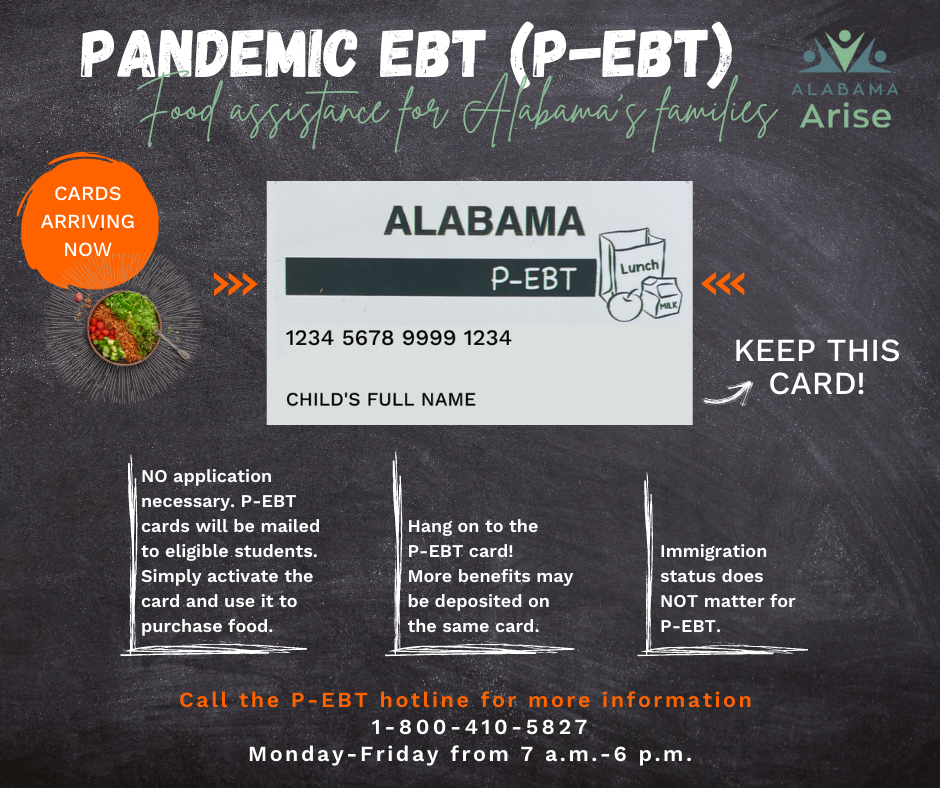

P-EBT replaces missed school meals with cash assistance that families can spend on groceries. P-EBT is delivered to schoolchildren on a debit-like card. For children too young for school whose parents receive food assistance under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), P-EBT appears on their parents’ EBT card.

No one has to apply for P-EBT. Instead, it is automatically sent to most children who were eligible for free or reduced-price meals during the 2020-21 school year. Immigrant children who are undocumented are also eligible for P-EBT. P-EBT doesn’t affect immigration status for either the parents or the children.

P-EBT has complicated eligibility rules. Congress revised P-EBT through a legislative process called reconciliation, which made the program more complex for many participants. Alabama has worked to make P-EBT as simple as possible, but the program remains confusing for many eligible families. Alabama offers a toll-free hotline for P-EBT questions at 800-410-5827. The hotline is available from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. Monday through Friday.

Who is eligible for P-EBT?

How schools provide school meals affects P-EBT eligibility. To qualify for P-EBT, a school-age child must attend a school participating in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP). The child also must have been eligible for free NSLP meals during the 2020-21 school year. Some schools provide universal free NSLP lunch and breakfast under a special option called community eligibility. Every child who attended those schools is eligible for P-EBT, no matter what their family income is. But other Alabama schools pay for free school meals with a summer feeding option that differs from community eligibility. Unlike community eligibility, this option does not automatically qualify children for P-EBT. (A list of Alabama schools that have adopted community eligibility is available here.)

Children who attend a school that provides free meals through an option other than community eligibility must get approved for free or reduced-price meals in an additional way to be eligible for P-EBT. This approval most often results from an approved school meal application or family participation in SNAP. This can be very confusing for parents, who rarely know which federal funding stream pays for their children’s school meals. Many parents didn’t apply for free meals because their children were already receiving them or were going to school remotely.

The 2020-21 school schedule also affects eligibility. Children approved for free or reduced-price meals under NSLP can receive P-EBT if they attended school remotely or partially remotely during the 2020-21 school year. To receive P-EBT for specific months, a child must have (1) attended a school that the state Department of Education listed as hybrid or virtual during those months or (2) attended remotely at parental request. Children who attended a school that was fully open and offering school meals are not eligible for P-EBT.

Can children who are too young to attend school qualify for P-EBT?

Young children in SNAP households also can qualify for P-EBT. Many children under age 6 who didn’t attend a public school still can receive P-EBT. They qualify if they live in a household that received SNAP assistance in any month between October 2020 and May 2021 and if a school in the child’s county was virtual or hybrid.

Young children’s benefits are calculated in the same manner as those for schoolchildren. These benefits are based on whether any school in their county was virtual or hybrid. Benefits for children under age 6 who receive SNAP and are not in school are retroactive only to October 2020. Congress passed legislation extending P-EBT to these children in October.

How much will P-EBT participants receive?

The amount of P-EBT assistance depends on the school’s 2020-21 schedule. The P-EBT amount is based on how the Department of Education defined the 2020-21 “learning plan” for the child’s school. Children whose school is defined as virtual receive $6.82 per day in benefits for 18 days per month or $122.76 for each academic month they’re listed as virtual. Children whose school is identified as hybrid receive $6.82 per day for nine days per month or $61.38 per month for each month their school is listed as hybrid.

The state updated schools’ status as “virtual,” “hybrid” or “fully in person” every two months. That means some children may receive different amounts for different months of the school year. Benefits are retroactive to August 2020.

How can Alabamians get P-EBT allotments for the school year and summer?

There are three rounds of P-EBT benefits. School-year P-EBT benefits went out in two rounds, each for approximately half of the 2020-21 school year. The first round of P-EBT benefits for schoolchildren went out in June, and the second round went out in August. Children under age 6 who receive SNAP and are not enrolled in school will receive their allotments later than schoolchildren. Officials will check their names against those of children in school (including pre-K) to ensure no one receives benefits twice.

Participants eligible for summer P-EBT benefits should receive them sometime in fall 2021. Schoolchildren are eligible for summer P-EBT if they were eligible for free or reduced-price NSLP meals, including through community eligibility, in May 2021. Aug. 31 is the deadline for parents to apply at their local school for 2020-21 free or reduced-price meals so their children qualify for summer P-EBT. Children who are under age 6 and not enrolled in school will be eligible for summer P-EBT if their families received SNAP assistance any time after October 2020. Eligible children will receive $375 each in summer P-EBT benefits.

What is the future of P-EBT?

Advocates are working hard to extend P-EBT into the future. Congress authorized P-EBT only for the 2020-21 school year and summer. However, Alabama Arise and other advocates are working hard to convince lawmakers to extend P-EBT into the future. Stay involved by signing up for updates and action alerts on these efforts from Alabama Arise and Hunger Free Alabama.

To help ensure children remain eligible for P-EBT if Congress extends it, many parents should apply for free or reduced-price school meals even if their school already provides free meals. Applications for free meals aren’t necessary for children attending schools already participating in the Community Eligibility Program.