MEDICAID IMPROVEMENTS

What you need to know…

- New Medicaid changes seek to improve health and cut costs by rewarding timely and preventive care.

- The statewide Integrated Care Network (ICN) is coordinating long-term care for about 23,000 Alabamians.

- Seven regional Alabama Coordinated Health Networks (ACHNs) are coordinating primary and specialty care for about 750,000 Alabamians.

- The ICN and ACHNs have Consumer Advisory Committees and consumer representatives on their boards.

- ACHNs have identified infant mortality, obesity and substance use disorders as top priorities for improvement.

Steps in the right direction

Recent changes in the way Medicaid members get their care are promising moves in the right direction. By rewarding prevention and appropriate, timely care, Medicaid hopes to improve health outcomes, while bringing costs down in the process.

The new plans can be a significant improvement over the old Medicaid system, if they keep the focus on better health. One way to improve the chances for success is to have a strong consumer voice at the policy table. The changes are happening on two tracks:

- Long-term care for people who need assistance with activities of daily living.

- Primary care for children and pregnant mothers.

Public policy is better and more responsive when people have a say in decisions that affect their health and well-being. And Alabama Medicaid reforms are lifting those voices.

Rethinking Medicaid long-term care

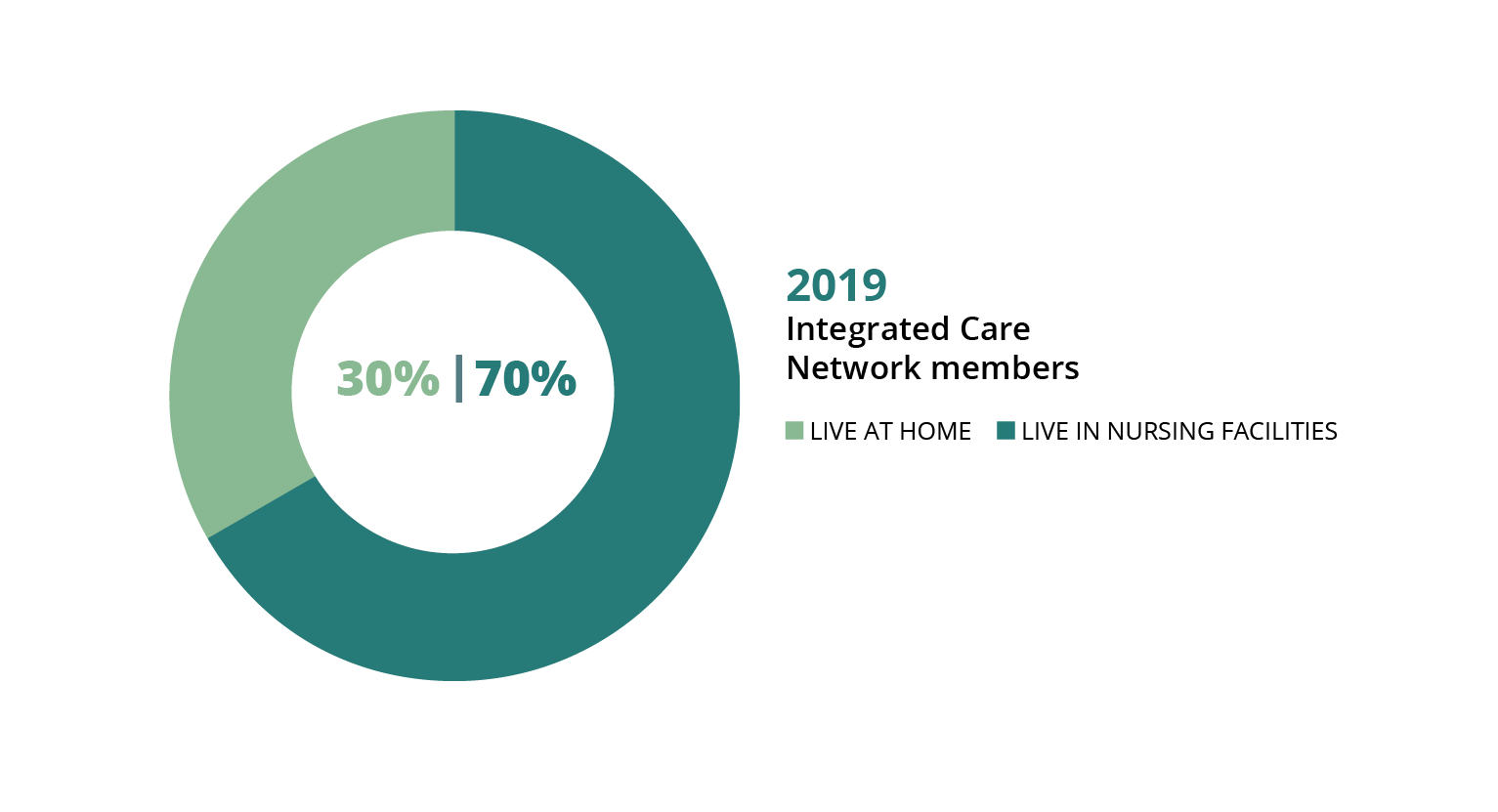

For long-term care patients, Medicaid has a new plan called the Integrated Care Network (ICN). The ICN coordinates care for Medicaid members who live in nursing facilities or receive certain home- and community-based waiver services. There are only about 23,000 of these members across Alabama, so one statewide ICN serves all of them.

For long-term care patients, Medicaid has a new plan called the Integrated Care Network (ICN). The ICN coordinates care for Medicaid members who live in nursing facilities or receive certain home- and community-based waiver services. There are only about 23,000 of these members across Alabama, so one statewide ICN serves all of them.

In 2019, roughly two-thirds of people served by the ICN lived in nursing facilities, and about one-third were living at home. The goal of the program is to help more people get long-term care services in their home and community, if that’s what they want. The ICN works with the 13 Area Agencies on Aging across the state to coordinate long-term care for Medicaid members who qualify.

The ICN also has a strong consumer voice at the policy table. Four consumer advocates serve on the governing board. And the Consumer Advisory Committee (CAC) includes eight consumer representatives. The chairperson of the CAC (Dr. Eric Peebles, featured below) receives home-based long-term care services through a Medicaid waiver.

SPOTLIGHT

Meet Dr. Eric Peebles

School officials in the New York community where Eric Peebles grew up tried every excuse in the book to prevent him from starting school. “We can’t find him an appropriate classroom aide,” they said. Or “his power wheelchair is a danger to the other students.”

It was the mid-1980s, and federally mandated special education was still a relatively new policy. But those officials didn’t know what they were getting into when they threw roadblocks in the path of Eric and his mom, Pat. Two years, multiple runarounds and a lawsuit later, Eric’s school district found itself under federal supervision, and all district administrators involved in his case lost their jobs. His mother was appointed to the search committee for their replacements.

Thanks to his mom, Eric got an early education in self-advocacy. That groundwork served him well 25 years later when he moved to Alabama to complete his doctorate and join the undergraduate faculty in rehabilitation and disability studies at Auburn University. His personal experience with spastic cerebral palsy (resulting from oxygen deprivation at birth) gives him an insider’s perspective on disability policy and services — and on stereotypes. One misconception he fights hard to dispel is the assumption that his advocacy is aimed solely at asserting his own rights and opportunities, rather than those of all people with disabilities.

‘Greater things to come’

When Eric moved here nearly 10 years ago, Alabama Medicaid’s long-term care services were so sparse that he maintained his residency in another state until the menu of services expanded. Today, he enjoys community self-sufficiency through his participation in the Alabama Community Transition (ACT) waiver. In addition to running his own research and consulting business, Accessible Alabama, Eric serves on the board of the Disabilities Leadership Coalition of Alabama and chairs the Medicaid Integrated Care Network (ICN) Consumer Advisory Committee. In 2019, Gov. Kay Ivey appointed him to the State of Alabama Independent Living Council.

Those long-ago school officials left a mark they couldn’t foresee. Among all his achievements, Eric counts the success of his own former students as a special point of pride. But his advocacy story is still being written, he says. “It feels like these accomplishments are forerunners of greater things to come.”

A regional approach to Medicaid primary care

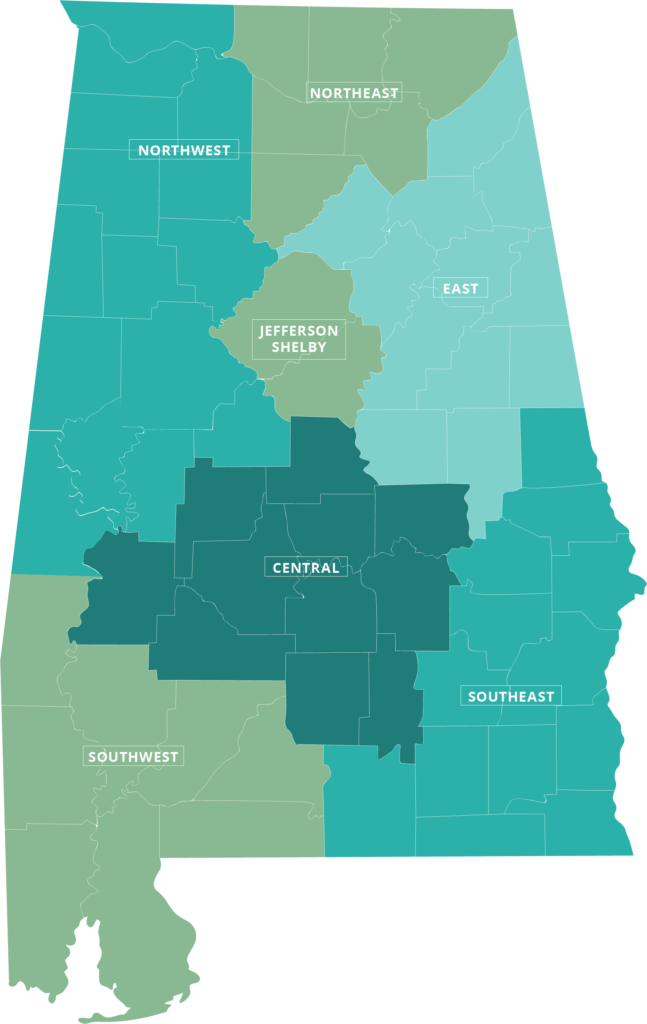

Under Alabama Medicaid’s new structure, seven regional Alabama Coordinated Health Networks (ACHNs) coordinate primary care for Medicaid children, pregnant mothers and people who receive family planning services. Primary care includes well-child visits; EPSDT (Early Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment) for children; adult screening, diagnosis and treatment; and preventive care.

Each member can choose a primary care doctor to be their “patient-centered medical home.” Each ACHN has a phone line to call when a Medicaid participant has a health problem. The basic idea is that nurses, social workers and care coordinators working with the primary care doctor can help people get the right care for the right problem without going to the emergency room whenever they get sick.

Medicaid ACHNs bring a new focus on consumer engagement and better health

The regional network plan gives Medicaid new tools for improving health outcomes. The ACHN can help patients identify health goals, create a care plan and connect with community resources that promote better health. The new plan serves about 750,000 Medicaid members across seven regions. Each ACHN has a consumer representative on its board, in addition to a Consumer Advisory Committee (CAC).

Bonus payments for doctors who reach quality benchmarks are another feature aimed at improving care. Each ACHN also is conducting Quality Improvement Projects (QIPs) targeting three health measures for improvement:

- Infant mortality

- Obesity

- Substance use disorders

SPOTLIGHT

Meet Audrey Trippe

Audrey Trippe, a resident of Attalla in Etowah County, has worked in mental health care since 2013, serving as a peer support specialist, peer supervisor, youth peer and certified addiction counselor. She and her husband are the proud parents of two boys, one of them a newborn.

Audrey considers herself in long-term recovery from major depression and substance use disorder. She has spent most of her young adulthood in the coverage gap, relying on urgent care clinics and the ER. Being heard has been a challenge.

“There have been times I’ve felt like a chart and not a person,” she says. “I’ve felt overmedicated at times because I couldn’t communicate what feelings were from my mental issues and what feelings were normal for substance use recovery.”

For a while, Audrey and her husband had enough income to purchase Marketplace insurance, which covered her first pregnancy. But a series of financial setbacks put her back in the gap — and her baby into Medicaid coverage. She qualified for Medicaid herself with her second pregnancy. Now that the baby is born, Audrey’s coverage will expire 60 days after delivery.

‘Great hope for the future’

Navigating these ins and outs, ups and downs has motivated Audrey to help others find their way. That’s why she said yes when a friend at the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program asked her to be a consumer representative for her local Alabama Coordinated Health Network (ACHN). She wants to be an “authentic voice” for consumers.

“I want to educate individuals about the options they have and teach them how to have helpful conversations with their own care providers,” she says.

While Audrey faces returning to the coverage gap when her pregnancy coverage expires, she maintains a positive outlook.

“I believe things are getting better all around, and I have great hope for the future,” she says. “There are still things that need to change, but change — like recovery — takes time.”

Priority for improvement

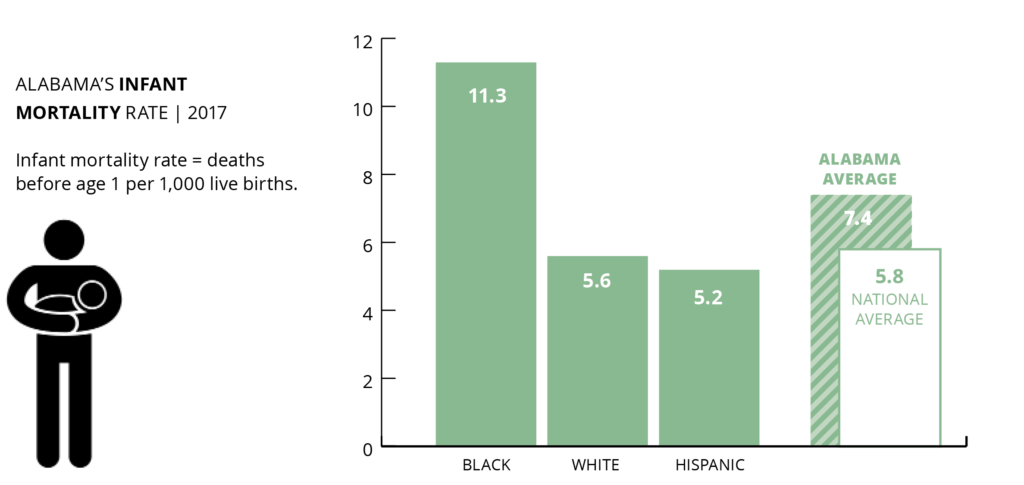

Infant mortality

Alabama’s regional Medicaid networks have identified infant mortality as a key target for improving health outcomes. That’s a promising step. Evidence from Medicaid expansion states shows that providing women continuous health coverage — not just during pregnancy — would make a life-saving difference. Lowering the high rate of African American infant deaths is the key to overall improvement.

National ranking: 45th

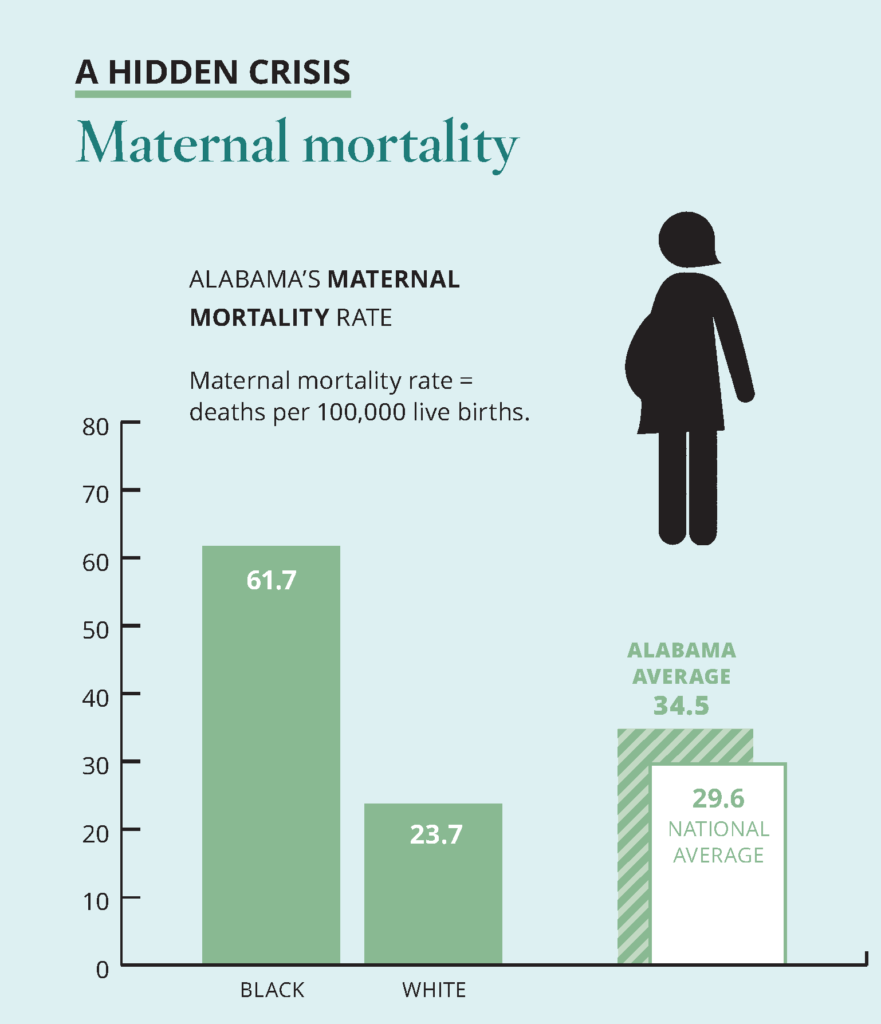

A hidden crisis: Maternal mortality

In late 2019, the Alabama Department of Public Health (ADPH) announced the infant mortality rate for 2018 at a record low 7.0 per 1,000 live births. National comparisons are not yet available. Alabama’s infant mortality rate is improving but remains one of the highest in the country, and racial disparity in birth outcomes is widening.

A particular concern is the continuing increase in the percentage of births with no prenatal care, which rose to 2.4% in 2018, ADPH reports.

The chief medical causes of infant death include congenital abnormalities, low birth weight and preterm births, Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) and bacterial sepsis, according to ADPH. Health researchers are discovering how social factors like place of residence, environmental influences and available resources play a role in determining different outcomes for different racial groups.

Maternal deaths in childbirth occur more rarely than infant deaths, but they are a stark indicator of racial disparities in health care. Black mothers in Alabama die in childbirth at nearly three times the rate of white mothers, and nearly double the overall statewide rate.

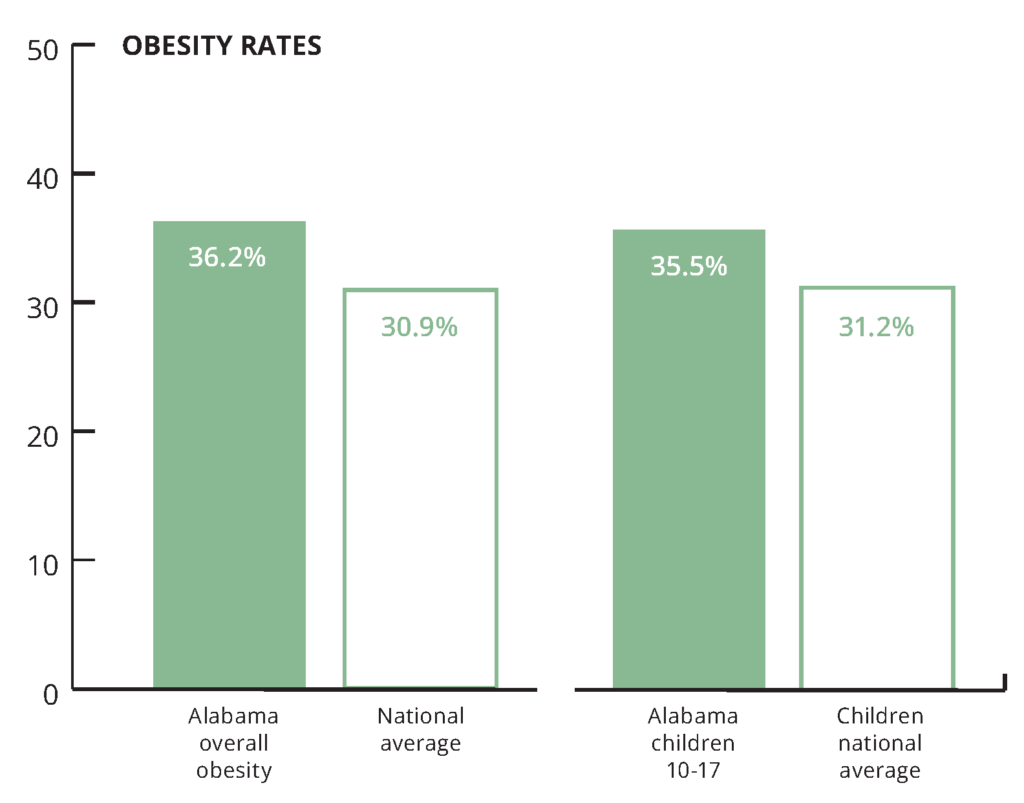

Priority for improvement

Obesity

Alabama’s regional Medicaid networks are working to reduce the state’s obesity rate. Extending Medicaid coverage to adults with low incomes would allow thousands more Alabamians to benefit. That would mean healthier families and a healthier workforce.

National ranking: 45th

A leading cause of obesity is food insecurity, or the inability to provide adequate food for one or more household members because of lack of resources. Families experiencing food insecurity may rely on low-cost, high-energy foods and beverages, which can lead to overconsumption of calories and result in obesity.

16.3% of Alabama households experienced food insecurity in 2019, for a national ranking of 46th. The national average was 12.3%.

Healthy foods, such as fresh fruits and vegetables, are more expensive and less available in some communities than in others. A CDC study found that only 6.1% of Alabama adults meet the daily vegetable intake recommendation. And only 8.8% of Alabama adults meet the daily fruit intake recommendation. Medicaid programs in other states are exploring ways to make healthy foods more accessible and affordable where people live, work, learn and play. (Source: America’s Health Rankings, 2019 Health of Women and Children Report)

Priority for improvement

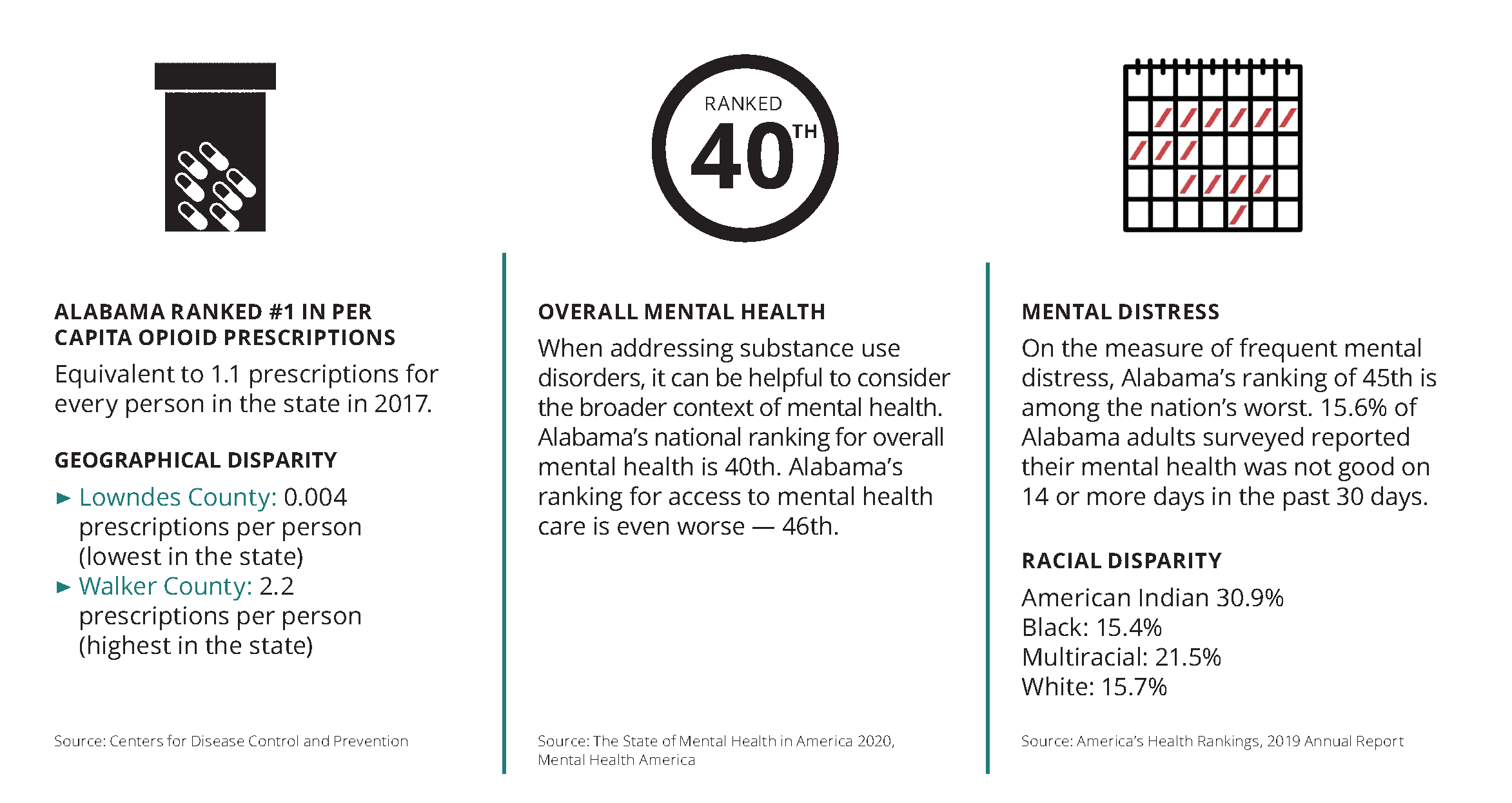

Substance use disorders

Alabama’s regional Medicaid networks seek to boost the availability of treatment for

substance use disorders. In the past five years, drug deaths in Alabama increased 37%, from 11.7 to 16.1 deaths per 100,000 people. Despite the increase, Alabama’s drug death rate remained below the national average of 19.2 deaths per 100,000. (Source: America’s Health Rankings, 2019 Annual Report)