The auto industry plays a crucial role in Alabama’s economy. In many stakeholders’ views, the industry has benefited the state in the 30 years since Mercedes moved to town. State media outlets routinely report glowing headlines like:

- “Alabama’s modern auto industry becomes state’s top export 25 years after its birth.”[51]

- “Alabama’s auto industry looks to add more than 3,000 new jobs in wake of COVID.”[52]

- “The great Alabama automobile success story.”[53]

Beyond the headlines, the auto industry’s enormous benefit to the state’s economy is clear. Today, Alabama is one of the top five states for auto manufacturing, producing 1.3 million cars and light trucks in 2022. That same year, Toyota, Honda and Hyundai combined to produce 1.5 million auto engines. As a result, auto vehicles are now Alabama’s top export, with sales to more than 70 nations totaling $9 billion to $10 billion.[54] [55] In 2018 alone, Honda and its direct Tier 1 suppliers by themselves generated more than $1 billion in earnings to Alabama households, accounted for $12 billion in annual economic impact and contributed 5.4% of Alabama’s entire GDP.[56]

Moreover, the industry continues to grow its footprint in Alabama. In 2021, the governor’s office reported 42 new auto industrial development projects, which promised to create 1,426 new jobs and $536,255,265 in new capital investment.[57] In addition, the Alabama Department of Commerce recently boasted that the state’s growing automotive supplier network, which now includes 150 major companies, created around 26,000 vehicles in 2021.[58] [59]

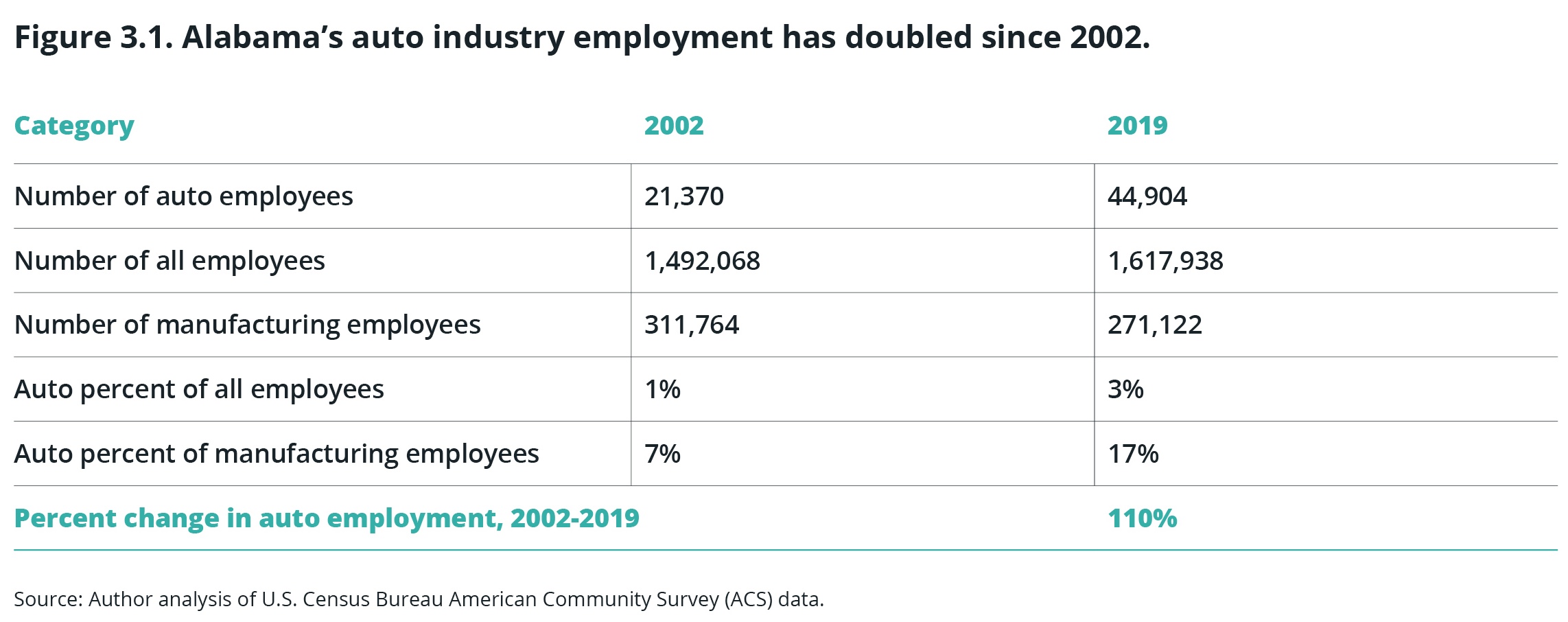

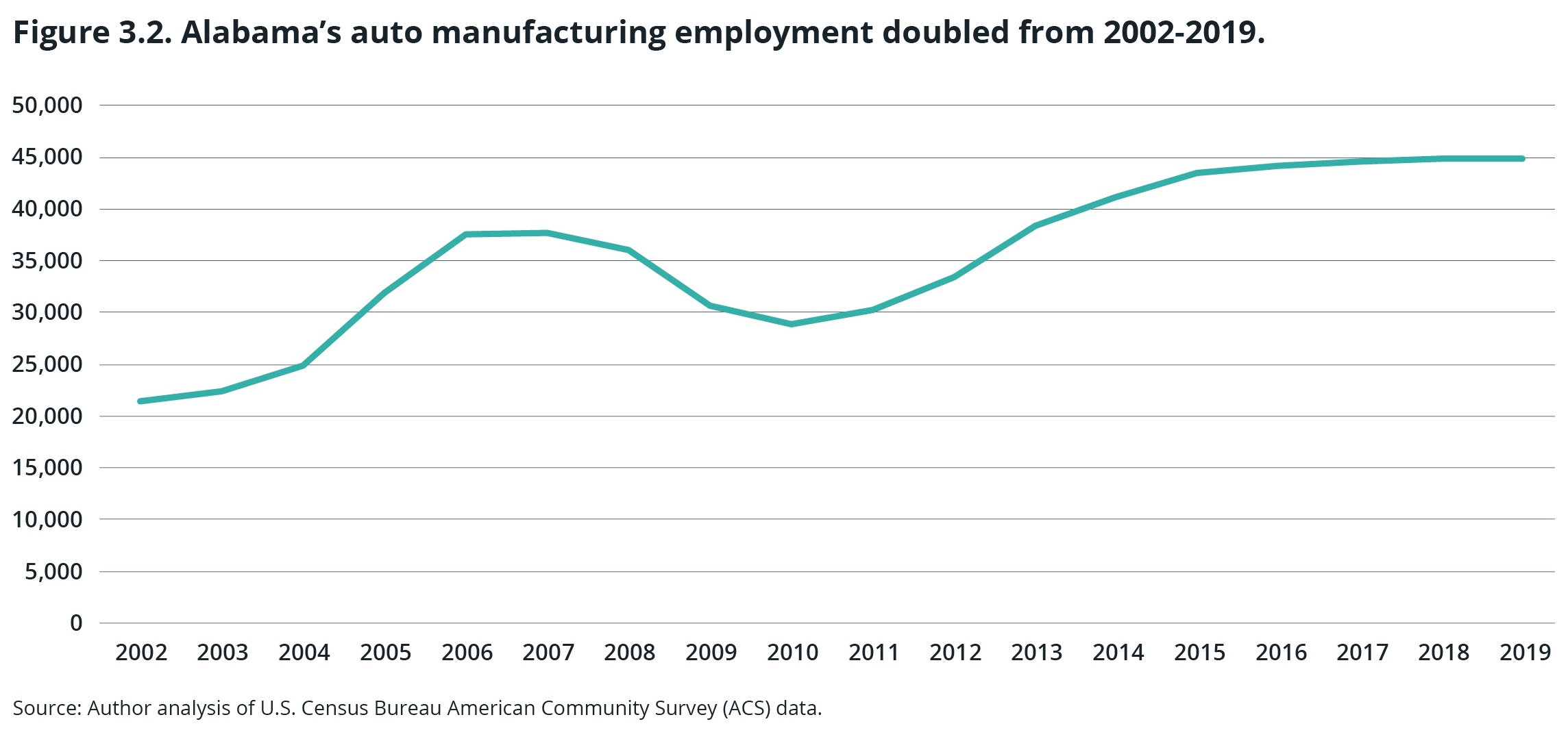

Alabama’s auto industry also has become a major employer. By the numbers, the auto industry is among Alabama’s five largest employers, with 44,904 workers on payroll in 2019. That means about one in every six Alabamians working in the manufacturing sector are employed in the auto industry. (See Figure 3.1.) Even more importantly, the auto industry has seen exceptional growth over the past 20 years, more than doubling the number of employees between 2002 and 2019. This occurred despite the economic damage wrought by the Great Recession, which significantly reduced demand for cars and trucks. (See Figure 3.2.) As Figure 3.1 shows, Mercedes locating in Alabama more than fulfilled the expectations of leaders and community members in 1993. The goal of reaching 15,000 to 17,000 jobs by 2003 was met early.

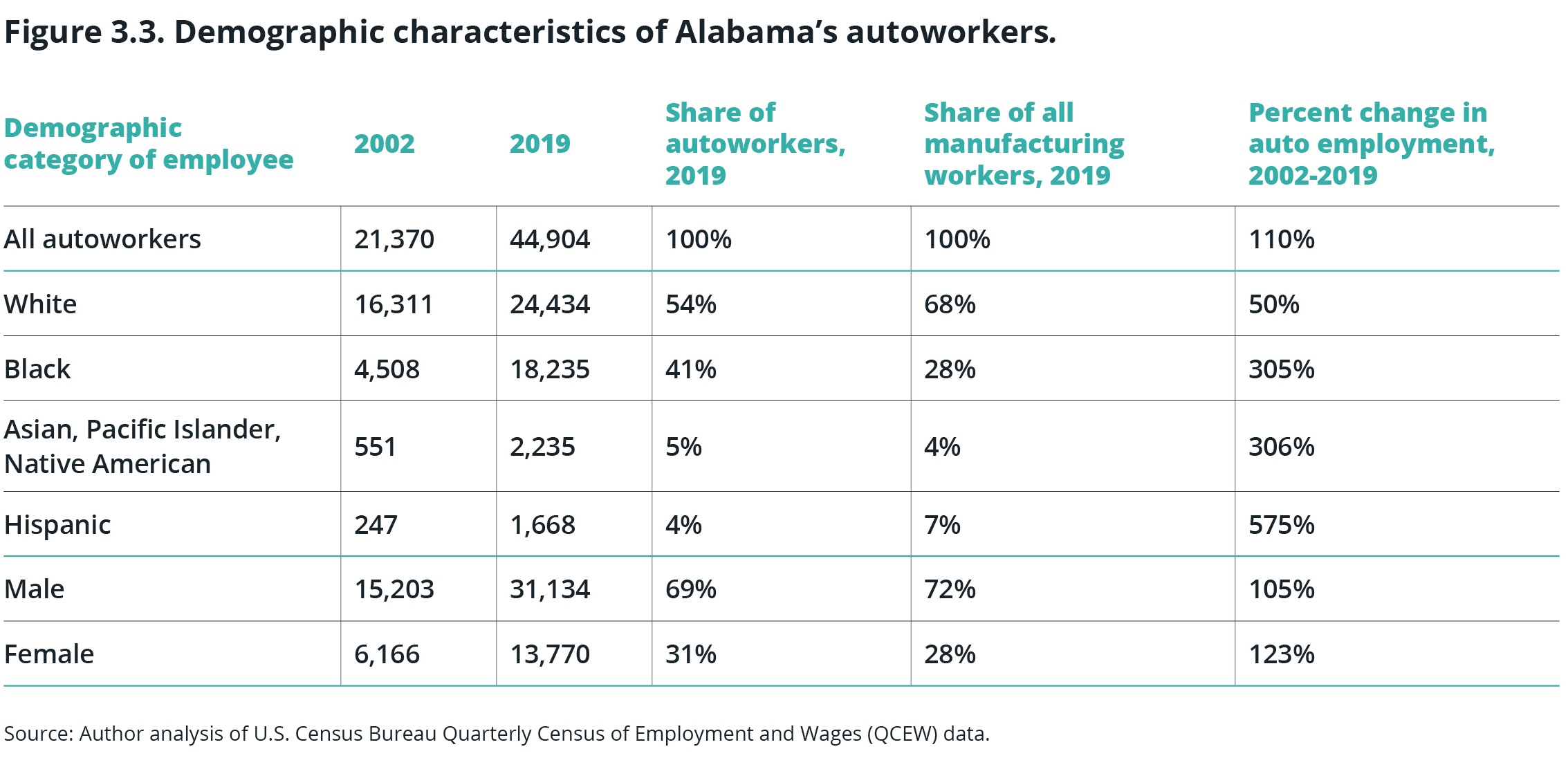

Alabama’s auto industry also has a more demographically diverse workforce than the state’s manufacturing sector as a whole. As seen in Figure 3.3, Black workers account for 41% of those employed in the auto industry, compared to a little more than a quarter of all manufacturing employees. In addition, women make up 31% of the auto industry workforce, compared to only 28% in the manufacturing sector overall.

Moreover, these trends are improving, thanks to targeted hiring and training efforts across Alabama’s auto industry. Examples include customized programs spearheaded by Alabama Industrial Development Training (AIDT), Alabama’s workforce training agency;[60] the creation of Apprenticeship Alabama (designed to provide classroom instruction and on-the-job training); [61] [62] the creation of AlabamaWorks (a workforce development partner); [63] [64] and the creation of the Alabama Robotics Technology Park (a facility that trains auto manufacturing and other industry workers).[65] [66] In a sign of this improvement, Black employment in the auto industry has quadrupled in size since 2002. That is a 305% growth rate, compared to the 50% increase in white auto employment. Over the same period, Hispanic auto employment has grown by 575%, and the number of women in the auto workforce has grown by 123%. (See Figure 3.3.)

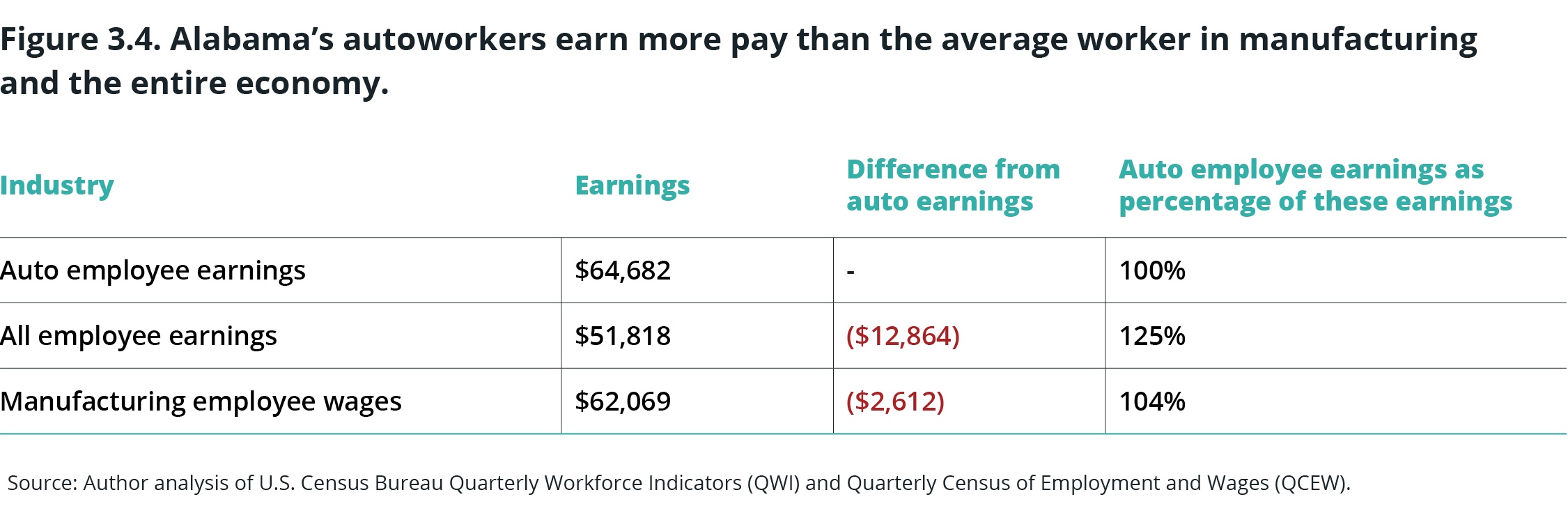

Not only does Alabama’s auto industry provide a large number of jobs for state residents, it also generally provides good-paying jobs (though this is becoming less true over time; see Section 4). As seen in Figure 3.4, Alabama’s auto industry pays more than jobs in both the broader state economy and in the state’s manufacturing sector. The average autoworker in Alabama earns 25% more than the state’s average worker and 4% more than the average manufacturing worker.

Bottom line: As anticipated when they were first recruited to locate in Alabama, the auto industry pays Alabama workers better wages than they could earn in other parts of the economy. These wages are a significant contributor to a rise in state manufacturing wages over the past 20 years.[67]

The auto industry anchored Alabama’s economic transformation

Aside from these direct benefits, the auto industry also has played a crucial role in galvanizing Alabama’s long-term economic transformation. In the 1970s and 1980s, Alabama’s core industrial sectors – mostly steel, textiles, coal mining and paper manufacturing – entered long-term decline, with several important regional employers shuttering their facilities and moving their jobs to lower-cost locations in developing nations.

This shift was particularly noticeable considering western Jefferson and eastern Tuscaloosa counties’ economic reliance on mining in multiple communities.[68] Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the mining industry was drastically reducing manpower nationally. Mining companies reduced the industry’s workforce by more than 25% in the 1980s, with coal mining losing 46% of workers.[69] Communities throughout Alabama felt the pain of sector-wide economic contraction, and officials sought substitute industries that could soften the blow and prevent population decline and consequent community damage. Passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 accelerated these trends, especially for steel and textiles.

When Mercedes announced it was considering Alabama for its first North American auto facility in 1993, state economic development officials hoped to use the German car manufacturer as an anchor to transition Alabama’s economy toward more advanced manufacturing – and the higher-wage, higher-skilled jobs that come with it. They also hoped to revitalize struggling coal and textile communities in Jefferson and Tuscaloosa counties.

Thirty years after the first M-Class rolled off the assembly lines in Vance, it’s clear that these hopes have become reality. For years, Alabama has been able to refer to itself as the “center of the Southeast’s auto industry” and the “Detroit of the South.”[70] Just a few years after Mercedes opened its first plant in the state, Honda followed suit (2001), followed by Hyundai (2005), as well as many auto parts manufacturers, including Toyota.[71] As a result of the state’s industrial transformation, companies in the broader manufacturing sector have been able to count on availability of a trained and capable workforce in advanced manufacturing, including the aerospace sector. For example, certainty of the state’s workforce availability was a motivating factor in Airbus’ choice of Mobile for a major plant investment: “We never had a doubt we’d find the skilled workforce we need to produce our aircraft.”[72]

Additional sections

Executive summary

Executive summary

Introduction

Introduction

The high stakes and big bet on Alabama’s auto industry

The high stakes and big bet on Alabama’s auto industry

A wheel in the ditch: Autoworkers see falling pay

A wheel in the ditch: Autoworkers see falling pay

A wheel in the ditch: Pay gaps and occupational segregation

A wheel in the ditch: Pay gaps and occupational segregation

A wheel in the ditch: Economic impact of falling wages and the pay gap

A wheel in the ditch: Economic impact of falling wages and the pay gap

A wheel in the ditch: Working conditions worsen

A wheel in the ditch: Working conditions worsen

The auto industry and Alabama’s low-road economic development approach

The auto industry and Alabama’s low-road economic development approach

What we should do next

What we should do next

Research design and methodology

Research design and methodology

[51] Stephen Quinn, “Alabama’s modern auto industry becomes state’s top export 25 years after its birth,” ABC 33/40 (Feb. 15, 2023), https://abc3340.com/news/local/alabamas-modern-auto-industry-becomes-states-top-export-25-years-after-its-birth.

[52] William Thornton, “Alabama’s auto industry looks to add more than 3,000 new jobs in wake of COVID,” AL.com (June 2, 2021), https://www.al.com/business/2021/06/alabamas-auto-industry-looks-to-add-more-than-3000-new-jobs-in-wake-of-covid.html.

[53] Clanton Advertiser, “The great Alabama automobile success story,” Clanton Advertiser (Dec. 7, 2009), https://www.clantonadvertiser.com/2009/12/07/the-great-alabama-automobile-success-story.

[54] “Automotive,” Made in Alabama, https://www.madeinalabama.com/industries/industry/automotive.

[55] Autos Drive America & American International Automobile Dealers Association, International Automakers and Dealers in America: Economic Impact Report 2022, https://www.autosdriveamerica.org/economic-impact/2022/ADA_2022_8.5X11_national.pdf.

[56] Honda Manufacturing of Alabama, “Honda Economic Impact Study,” https://www.hondaalabama.com/img/mediahub/files/Honda-Economic-Impact-Study.pdf.

[57] “New & Expanding Industry Announcements, 2021 Report,” Made in Alabama (2022), https://governor.alabama.gov/assets/2022/05/2021-New-Expanding-Industry-Report.pdf.

[58] “Automotive,” supra note 54.

[59] Dawn Azok, “Job training programs fuel growth of Alabama auto industry,” Made in Alabama (Oct. 5, 2017), https://www.madeinalabama.com/2017/10/job-training-programs-fuel-growth-of-alabama-auto-industry.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Dawn Azok, “Apprenticeship Alabama aims to invest in workers,” Made in Alabama (Oct. 20, 2016), https://www.madeinalabama.com/2016/10/apprenticeship-alabama.

[62] Azok, supra note 59.

[63] Jerry Underwood, “State debuts unified workforce system, AlabamaWorks,” Made in Alabama (Nov. 16, 2016), https://www.madeinalabama.com/2016/11/alabama-works.

[64] Azok, supra note 59.

[65] Jerry Underwood, “Alabama Robotics Park Phase 3 center readies for training,” Made in Alabama (April 11, 2016), https://www.madeinalabama.com/2016/04/alabama-robotics-park-phase-3.

[66] Azok, supra note 59.

[67] Analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics QCEW data, available at https://www.bls.gov/cew/downloadable-data-files.htm.

[68] Alabama Department of Labor, Alabama Mine Map Repository: Directory of Underground Mine Maps (2013), https://www.labor.alabama.gov/Inspections/Mining/Directory_of_Mine_Maps_2013.pdf (listing more than 500 mine sites in Jefferson and Tuscaloosa counties).

[69] Lois M. Plunkett, “The 1980s: A Decade of Job Growth and Industry Shifts,” Monthly Labor Review, Bureau of Labor Statistics (Jan. 1990), 6, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/1990/09/Art1full.pdf.

[70] Ruckelshaus & Leberstein, supra note 16.

[71] Ibid.

[72] Mark Arend, “Alabama Airbus Project Adds Lift to Mobile’s Aerospace Sector,” Site Selection (Jan. 2017), https://siteselection.com/issues/2017/jan/alabama-airbus-project-adds-lift-to-mobiles-aerospace-sector.cfm.