Auto plants in Alabama have made a significant contribution to the state’s economy. But the big bet and significant investment in the form of corporate subsidies has only partly paid off. This is in part because the state’s weak worker protections have not mandated employment standards that would ensure better work conditions and equitable pay for workers despite gender or race. Below the surface of rosy sales and profit figures and flattering media profiles about the industry, Alabama’s autoworkers have lived through a long-term decline in wages and earnings, stunning gaps in pay across racial and gender lines, and deteriorating conditions on some shop floors. Taken together, the ways the auto industry has failed to live up fully to the hopes and promises of 1993 have cost Alabama’s workers and the overall state economy tangibly and measurably.

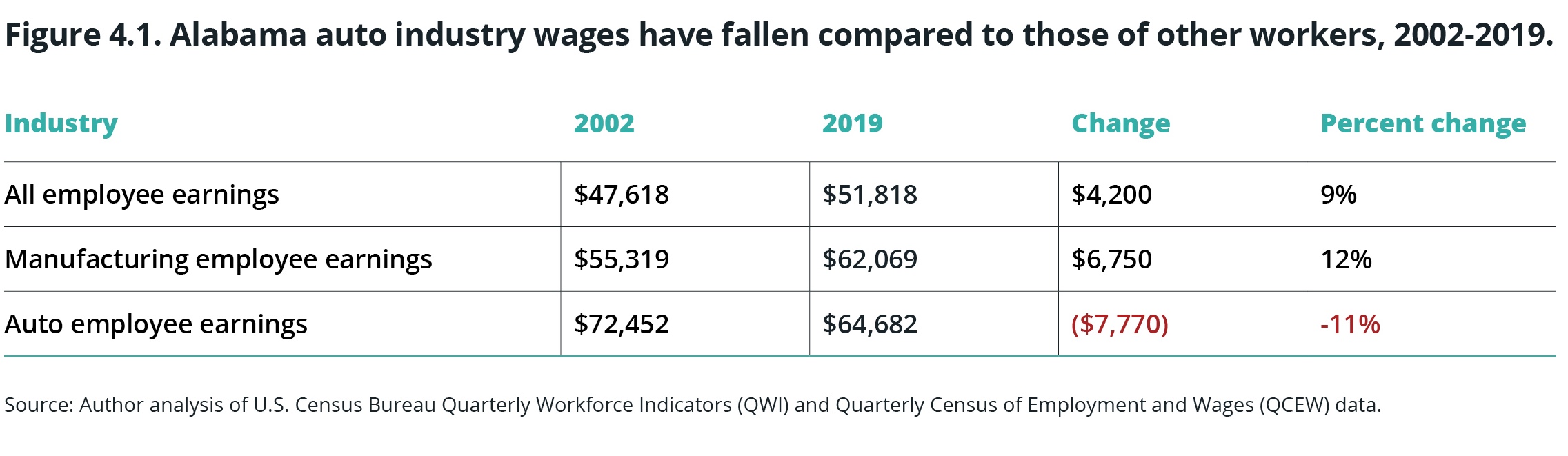

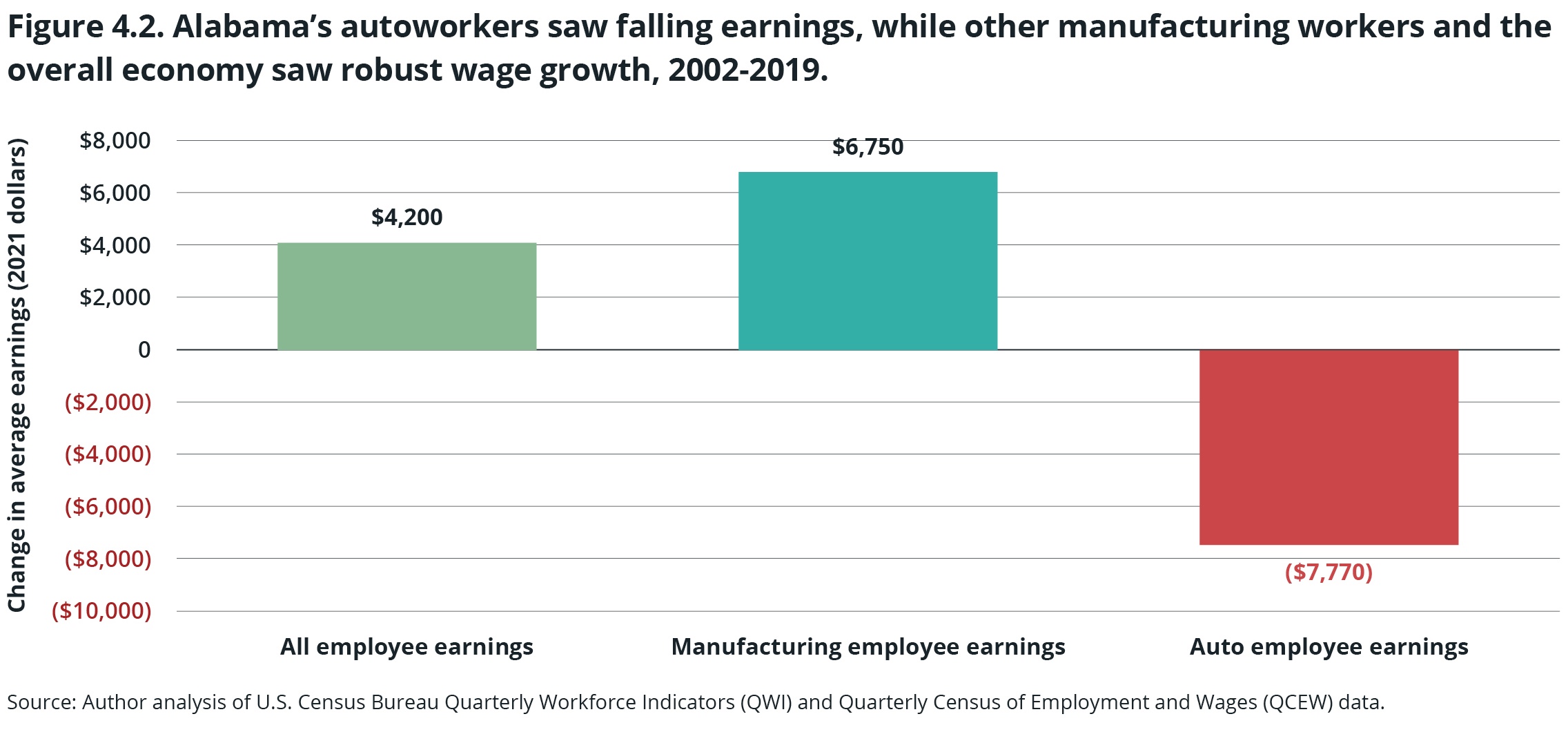

Most critically, Alabama’s autoworkers have lived through a significant and long-term decline in pay and earnings over the past 20 years. To be precise, autoworkers’ real wages (when adjusted for inflation) have fallen by $7,700 since 2002 – an 11% drop. (See Figures 4.1 and 4.2.) Despite rising profits for the auto companies and robust economic growth in the years following the Great Recession, Alabama’s autoworkers are earning less than they did a generation ago, while the cost of living and inflation have continued to rise.

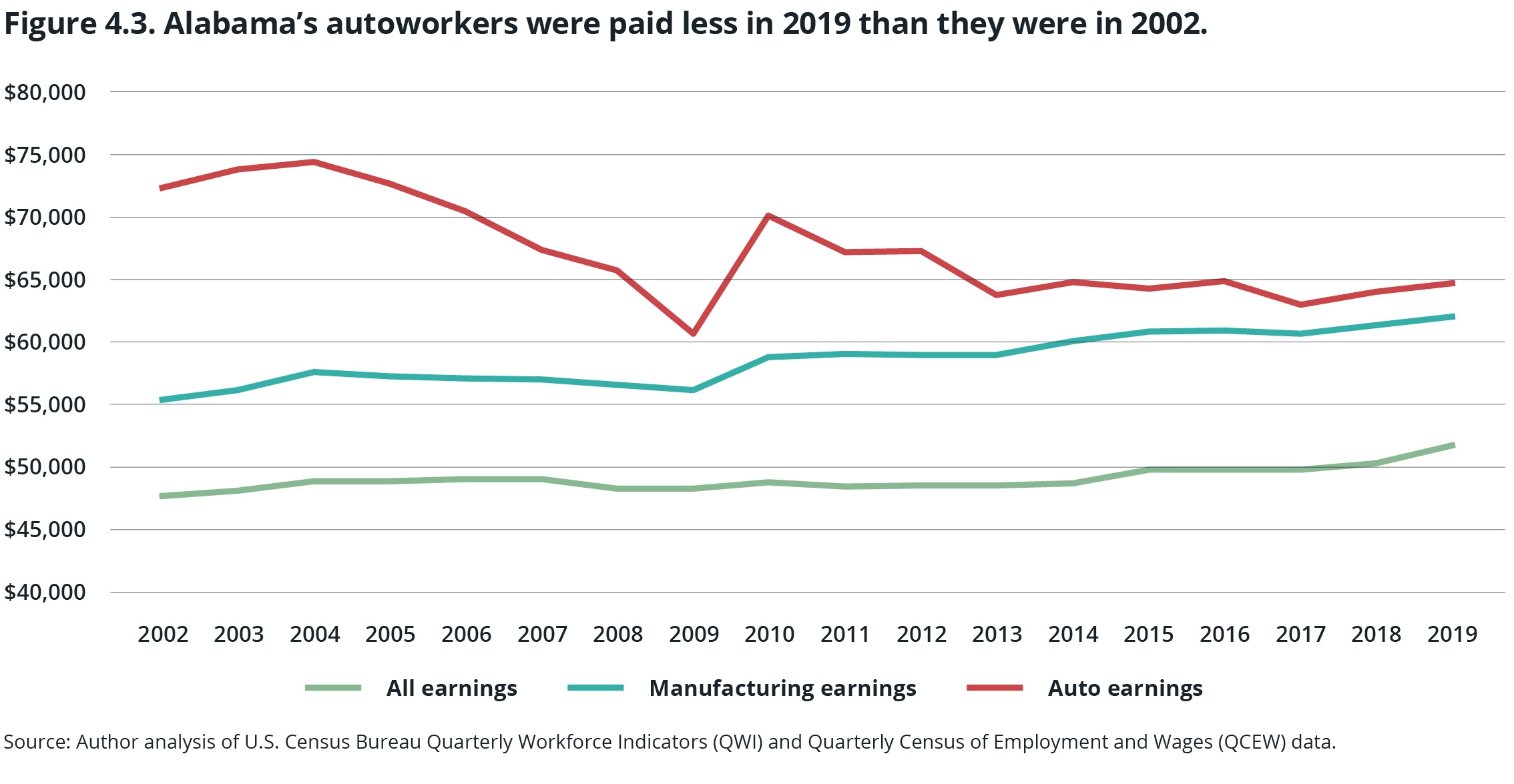

This precipitous drop in auto wages is especially stark compared to the wage growth seen by workers in the rest of Alabama’s economy. While the auto industry indeed still pays its workers a higher wage than they can earn in the rest of the economy, other industries – especially manufacturing – are catching up, thanks in large part to the drop in autoworker pay over the past 20 years. (See Figures 4.2 and 4.3.) At the same time as auto wages fell by $7,700, Alabama workers in the overall economy saw their wages rise by $4,200, and those employed in the broader manufacturing sector saw them rise by $6,750.

In the early years, the auto industry paid its workers a significant wage premium compared to the rest of the economy. For example, the average Alabama autoworker earned $72,452 in 2002 – about $25,000 more than what the average worker earned in the state economy that year ($47,618) and $17,000 more than what the average manufacturing worker earned ($55,319).

Yet by 2019, the autoworker wage premium shriveled, as the auto industry’s wages declined and other industries began to pay more. In 2019, Alabama’s autoworkers earned $64,682 – just $2,600 more than the average manufacturing worker in the state.

Autoworkers get paid less in Alabama than in the nation as a whole

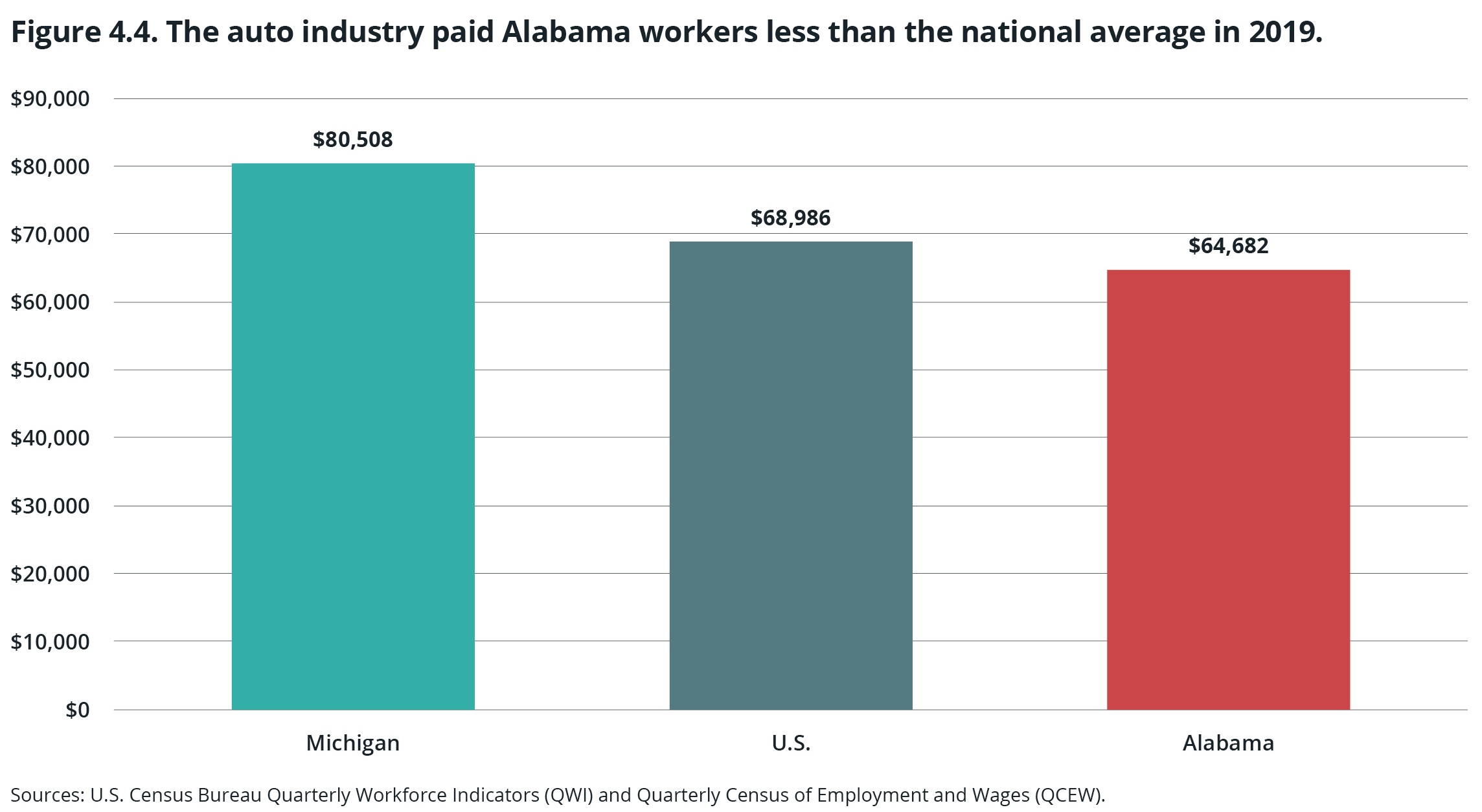

Not only are Alabama’s autoworkers getting paid less than they did 20 years ago, but they also continue to earn less than other autoworkers across the rest of the country. In 2019, Alabama’s auto plants paid their employees about $4,200 less in annual wages for the year than the national average of $68,896 – an earnings gap that’s remained largely consistent over the past 20 years. Compared to the traditional auto manufacturing heartland of Michigan, the pay gap looks even more glaring. Alabama’s autoworkers earned nearly $16,000 less in 2019 than those in Michigan. (See Figure 4.4.)

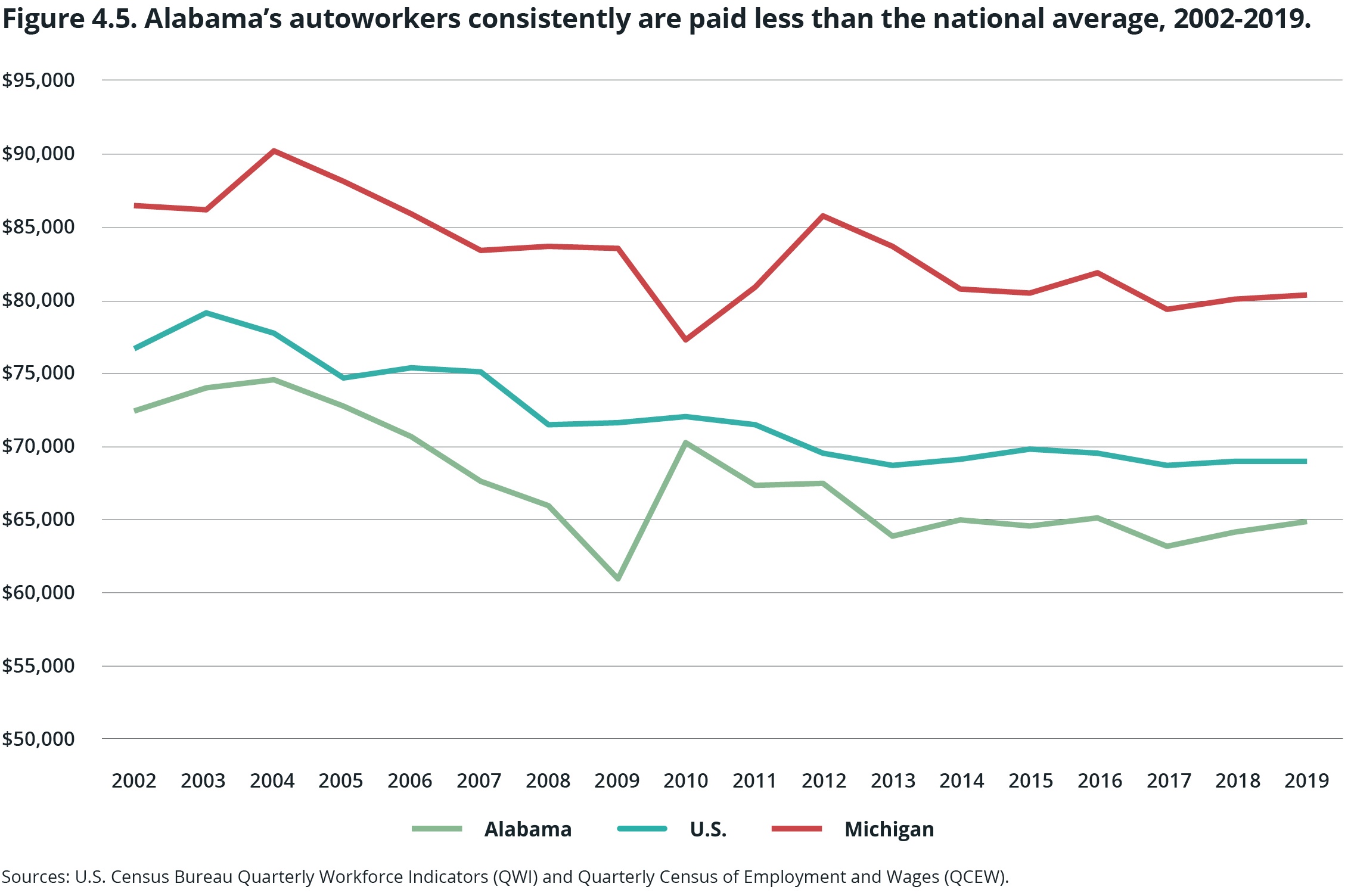

Taking a historical view, Alabama’s autoworkers have been living with these geographic pay gaps for 20 years. They’ve never earned the national average or close to heartland wages for their work in Alabama’s auto plants. (See Figure 4.5.) Magnifying the challenge, the auto industry has cut worker wages across the country as part of long-term disinvestment in labor over the past 20 years, trapping Alabama’s autoworkers in this national trend of labor disinvestment and declining pay. A range of factors have contributed to this industry-wide wage decline, including restructuring of the American auto industry after 2009, shifts in overall compensation packages (especially health insurance), and collective bargaining agreements that changed the entry-level wage for new auto employees.[73]

But the bottom line for Alabama’s workers is clear: Their wages keep shrinking. And because Alabama’s auto employees started out earning lower wages ($72,452 in 2002) than their average national counterparts ($76,785) or heartland autoworkers ($86,711), these earnings losses have hit Alabamians harder, leaving them with less money to cover the rising costs of living.

Auto wages fall while corporate profits rise

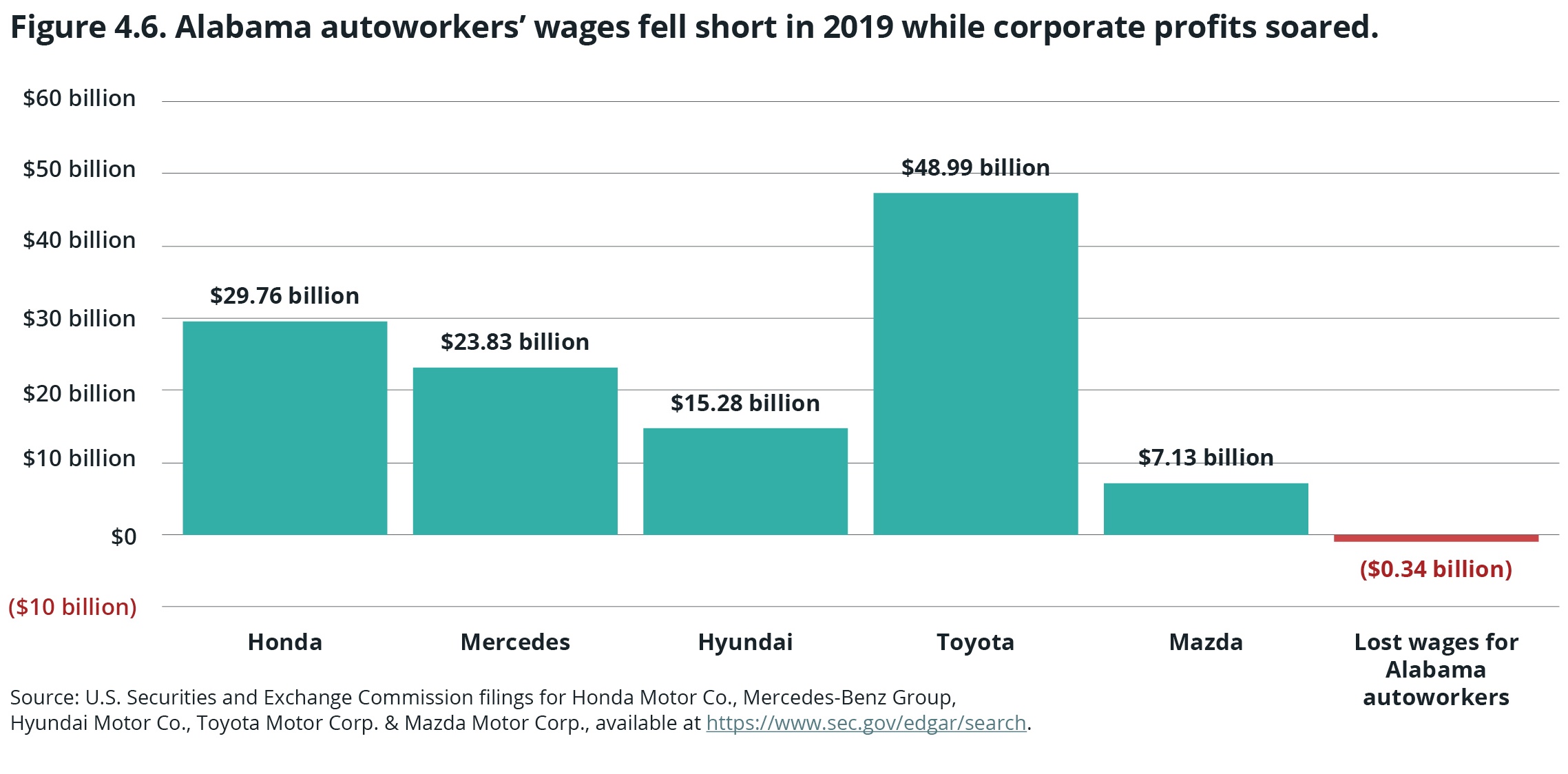

Alabama’s autoworkers have seen 20 years of declining wages while, at the same time, auto companies are experiencing record profitability. In 2019, the average employee in an Alabama auto plant earned 11% ($7,700) less per year than in 2002. This disconnect between worker productivity and pay impacts every worker across Alabama’s auto industry.

Adding together the average $7,700 in earnings lost by each of Alabama’s 44,904 auto employees translates into a total of $349 million in missing wages in 2019 alone. These are wages that could have gone into the pockets of Alabama autoworkers and their families but instead were extracted from the state’s economy.

Even more troubling, these missing wages came at a time when Alabama’s auto industry continued to experience record profitability. In 2019, Alabama’s five biggest auto manufacturers – Honda, Mercedes, Hyundai, Toyota and Mazda – together earned more than $127 billion in profits globally. Given profits of this magnitude, it seems reasonable to ask why automakers didn’t pay Alabama workers at least what they were making 20 years before. After all, $349 million in missing wages is a comparative drop in the bucket with profits like these. Paying Alabama’s autoworkers the same rate they made in 2002 would have equated to less than 0.3% of these companies’ profits.

Shortly before this report went to print, Honda, Hyundai and Toyota announced wage increases at their plants. This move came after the United Auto Workers negotiated substantial pay increases with Detroit automakers. These improvements are a good start and should serve as the foundation for further increases. These pay increases also show that wins for unionized workers help raise the standard for worker treatment across the sector.

Additional sections

Executive summary

Executive summary

Introduction

Introduction

The high stakes and big bet on Alabama’s auto industry

The high stakes and big bet on Alabama’s auto industry

The ways the bet on auto benefited Alabama

The ways the bet on auto benefited Alabama

A wheel in the ditch: Pay gaps and occupational segregation

A wheel in the ditch: Pay gaps and occupational segregation

A wheel in the ditch: Economic impact of falling wages and the pay gap

A wheel in the ditch: Economic impact of falling wages and the pay gap

A wheel in the ditch: Working conditions worsen

A wheel in the ditch: Working conditions worsen

The auto industry and Alabama’s low-road economic development approach

The auto industry and Alabama’s low-road economic development approach

What we should do next

What we should do next

Research design and methodology

Research design and methodology

[73] Joel Cutcher-Gershenfeld, Dan Brooks & Martin Mulloy, “The Decline and Resurgence of the U.S. Auto Industry,” Economic Policy Institute (May 6, 2015), https://www.epi.org/publication/the-decline-and-resurgence-of-the-u-s-auto-industry.